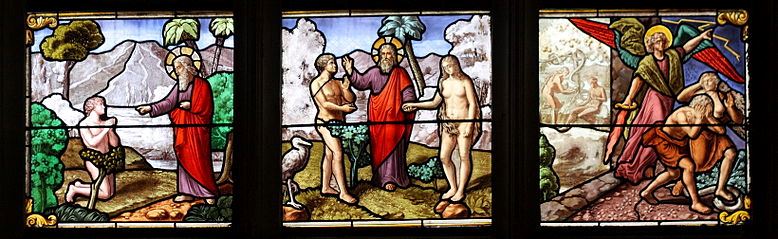

Cropped portion of “Bleiglasfenster in der Pfarrkirche Saint-Leu-Saint-Gilles in Paris” from GFreihalter. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported via Wikimedia Commons

Genesis was a very subversive text in its time, and in today’s context we often fail to understand its full significance. This was the message of a lecture by the biblical scholar Ernest Lucas at the Faraday Institute earlier this month. This is the last in a series of three from the Faraday summer course. If you want to find out more, the videos and audio of most of the lectures will be appearing on the Faraday website over the coming weeks*.

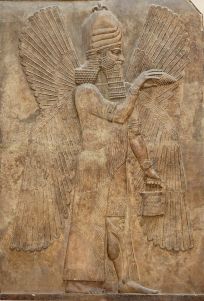

“Jiroft tabriz museum” from Fabien Dany – personal picture. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia CommonsAncient Near-Eastern culture** often used images of a well-watered paradise, of people made from clay plus a divine element, and a tree of life. Wisdom and immortality were highly sought after, and there was also the ambiguous significance of the serpent. Snakes could symbolise wisdom, the occult, or even evil.

Ancient Near-Eastern culture** often used images of a well-watered paradise, of people made from clay plus a divine element, and a tree of life. Wisdom and immortality were highly sought after, and there was also the ambiguous significance of the serpent. Snakes could symbolise wisdom, the occult, or even evil.

So the ancient Jewish origins story also makes use of these images, but subverts them for the author’s own purposes. People are made from clay – not to serve the Gods as slaves, but as precious royal image-bearers. Paradise is a place where those people come into relationship with God, and seeking wisdom for selfish reasons leads to great evil.

The Genesis account*** is highly structured, like the folk stories and educational literature of its time. It uses anthropomorphic language – God’s action is presented on the scale of a human drama – and it focuses on the formation of a society. Human beings are depicted as God’s representatives, created to be in relationship with him and worship him. The human plight is the result of our own rejection of God, and can only be restored by seeking true wisdom.

Winged genie with spath-(pollen), and pollen/spath-bucket before a Tree of Life panel, giving its blessing.”Blessing genie Dur Sharrukin” from Jastrow (2006). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Figurative literature can have a real historical event behind it, but the main purpose of this text is to convey theology or ontology****, not chronology. For example, on day six animals and people are described as being made from the dust – or produced by the land – and being given the breath of life. God then chooses mankind to ‘till and keep’, or ‘serve and preserve’ the earth. So as I’ve mentioned before, Genesis shows that our specialness comes not from our unique physical properties but from our relationship with God and the responsibilities that we have.

For Ancient Near-Eastern people, the truth of a text was functional. Does it help me cope with some aspect of life today? People believed that something existed by virtue of its having a functional or societal role, not its material properties. So for example when Adam is asked to name the animals, this is unlikely to refer to a moment when a man sat down and decided what to call every creature he could see. The context of this section of Genesis 2 is as part of God’s search for a partner for the man, so the purpose of the naming story is to highlight the fact that the only suitable partner for Adam is a woman.

The worldview of Genesis was so starkly different to the other creation stories of its time that it sparked a revolution. More specifically, the fact that science flourished in the West is partly down to Christian theology. An un-created, rational Creator made an ordered world, and made people in his image. It makes perfect sense for those people to explore the world and expect to understand it.

Cropped portion of “Bleiglasfenster in der Pfarrkirche Saint-Leu-Saint-Gilles in Paris” from GFreihalter. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported via Wikimedia Commons

So although Genesis is a difficult and seemingly primitive story, it contains such depth of meaning that it has been transforming society from its first telling right up to the present day. The challenge is to do the text justice by interpreting it as fully as possible. We may not have the key to every aspect of its symbolism, but its main messages are clear: God is present, and he created us to walk with him.

Further reading

- Ernest Lucas, “Interpreting Genesis in the 21st Century”, Faraday Papers, 11

- Ernest Lucas, Can We Believe Genesis Today? (IVP, 2005)

- Walton, Matthews & Chavalas (Eds), The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament (IVP USA, 2000)

- John H. Walton (Ed.) The Zondervan illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary (Old Testament) (Zondervan, 2002)

* Click the grey downward pointing arrow in the date column to bring up the most recent talks.

** The area roughly corresponding to the Middle East today, which back then included the civilisations of Egypt, Babylonia, Mesopotamia and Canaan, which are referred to in the Bible.

*** Up to chapter 11 verse 27, when the genre changes and the world depicted becomes recognisable as contemporary Near Eastern society.

****The nature of being.