Secuencia de AND by Pablo Gonzalez. Flickr. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Most weeks in my work as an immunologist, I am faced with the reality of our evolutionary origins. Someone will give a talk, describing the function of this or that receptor in humans and – in passing – will mention that the same receptor is seen in bacteria. Or (hoorah!) we find that an antibody, created to identify a protein in rats, nicely targets the same protein in human cells. Or an online search to identify a human DNA sequence ends up with a piece of armadillo DNA as the closest match (yes that did happen!)

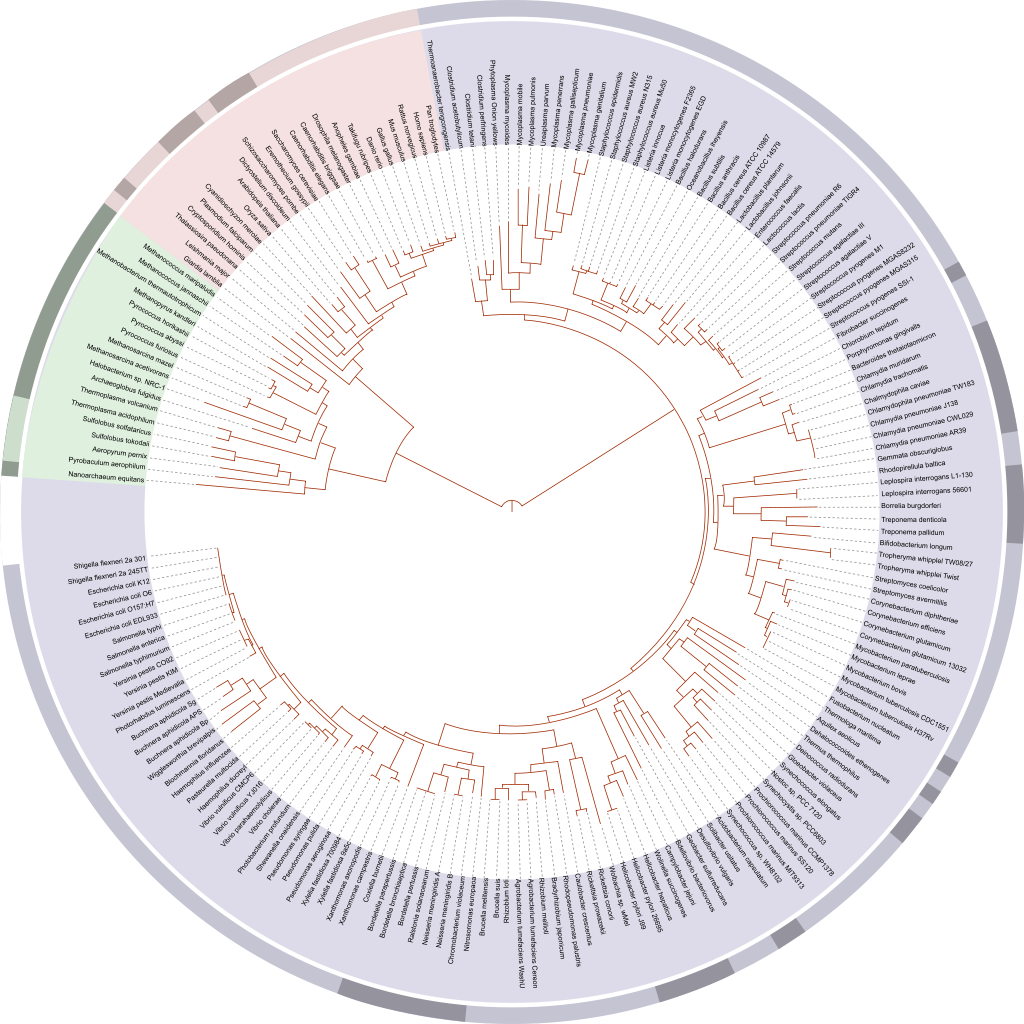

Tree of life By Ivica Letunic: Iletunic. Retraced by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal: LadyofHats [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

I used to think of illness as the product of a fallen world, but now I cannot. Firstly, I cannot see any biological reality to the Fall. Secondly, I have to accept that suffering is a necessary part of our creation. It seems God requires suffering for our creation. God has mandated our suffering. And what sort of God is that?

Lab technician in the Immunology department by Sanofi Pasteur. Flickr. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

I am also a doctor, and in fact I am writing this in between patients in an outpatient clinic. Every week, I see people with serious disability from neurological diseases. Some of these diseases arise because of genetic mutations interacting badly with our environment. The same process that made me able to flourish as a healthy human, “wonderfully made”, means the person in front of me experiences progressive contraction of their possibilities, capacities and hopes. Their health has, innocently and unwittingly, been sacrificed for mine. Many past humans have had limited lives, and animals before them, and simpler organisms before them, so that I might live life to the full. There is a terrible danger of feeling these blighted lives are instrumental for me; and that surely is not right.

I don’t often talk to other Christians about this, because in the past these views have caused hurt, confusion, or worse. I wish these thoughts would not nag away at me. But then the next experiment comes along, and there it is: the antibody we are using to identify a human target has just picked up something that the databases say belongs to a mouse. And a little later, I am seeing someone whose life is limited by a genetic mutation.

What helps me is reminding myself that we are all disabled. We are all, more or less, constrained and limited. Our myopic perspective is that some humans are gloriously able whilst others are terribly disabled, and we are full of a sense of unfairness. But I suspect that to God, all our capabilities are childishly tiny and His sense of fairness is more about his great and underserved gift of grace to us, rather than the differences between us. Perhaps what matters is how we work out our calling within our particular disability, as a member of His generous creation, open and full of possibilities.

Revd Professor Alasdair Coles is an academic neurologist in Cambridge, UK, whose primary research interest is in the immunology and treatment of multiple sclerosis. He is the Professor of neuroimmunology at Cambridge University, and has a small research team managing clinical trials and doing human immunological laboratory work. He also does clinical work for two days a week as a consultant neurologist at Addenbrooke’s Hospitals. Dr Coles was ordained priest in the Church of England in 2009 and is now a minister in secular employment at Addenbrooke’s Hospital. Dr Coles has also done some research on the neurological basis for religious experience, stemming from managing a small cohort of patients with spiritual experiences due to temporal lobe epilepsy. He is now engaged in a study, funded by the Templeton Foundation, of the spirituality of people with neurological disease in Cambridgeshire, and is editing a CUP book on religion in neurological disease.

Revd Professor Alasdair Coles is an academic neurologist in Cambridge, UK, whose primary research interest is in the immunology and treatment of multiple sclerosis. He is the Professor of neuroimmunology at Cambridge University, and has a small research team managing clinical trials and doing human immunological laboratory work. He also does clinical work for two days a week as a consultant neurologist at Addenbrooke’s Hospitals. Dr Coles was ordained priest in the Church of England in 2009 and is now a minister in secular employment at Addenbrooke’s Hospital. Dr Coles has also done some research on the neurological basis for religious experience, stemming from managing a small cohort of patients with spiritual experiences due to temporal lobe epilepsy. He is now engaged in a study, funded by the Templeton Foundation, of the spirituality of people with neurological disease in Cambridgeshire, and is editing a CUP book on religion in neurological disease.