Cropped from original. Credit: Annie Cavanagh. WellcomeCollection. (CC BY-NC 4.0)

I am an ex-cell biologist. Whilst I was a PhD student, it felt like cells were involved in every aspect of my life. I would grow cells, study cells, read about cells, spin them in centrifuges, look at them down a microscope, and visit them at 2am to take timepoints for particularly gruelling experiments. When I spoke to my relatives, the question ‘How are you?’ was often followed by: ‘How are your cells behaving?’. When I saw a newspaper headline: ‘Man trapped in cell for three days’, my first fleeting thought was ‘How on earth did they manage to squeeze a man into a cell in the first place?’

As a cell biologist, I performed experiments on cells, or on parts of cells. To be able to do this, I needed to grow millions of living cells. I found the whole process of growing cells (also known as cell culture) fascinating.

The lab I grew my cells in was a containment level two tissue culture lab, in which the safety procedures were much stricter than in the normal lab. The outside door was locked with a keypad that only lab-users knew the passcode to. We all had blue lab coats which stayed in the lab and cell culture procedures took place in special safety cabinets, with a flow of air and a protective glass screen. I once learned the hard way that if you attend A&E and say you’ve had a needlestick accident in a CL2 lab, you skip right to the front of the queue.

The cells I worked on were called SW480 cells. They could be stored in a freezer at minus 150oC for years on end, until I decided to ‘bring them up’ to the lab, as if waking them from a long, very cold, sleep. Once they were in the right conditions in my flask, they would then grow and multiply and I could then use them in my experiments. I could even prepare them to be stored in the freezer once again to ensure future stock levels were plentiful (or if I wanted to go on holiday). I found it absolutely amazing that these living cells could not only survive at such cold temperatures, but could also adapt to living at 37oC again.

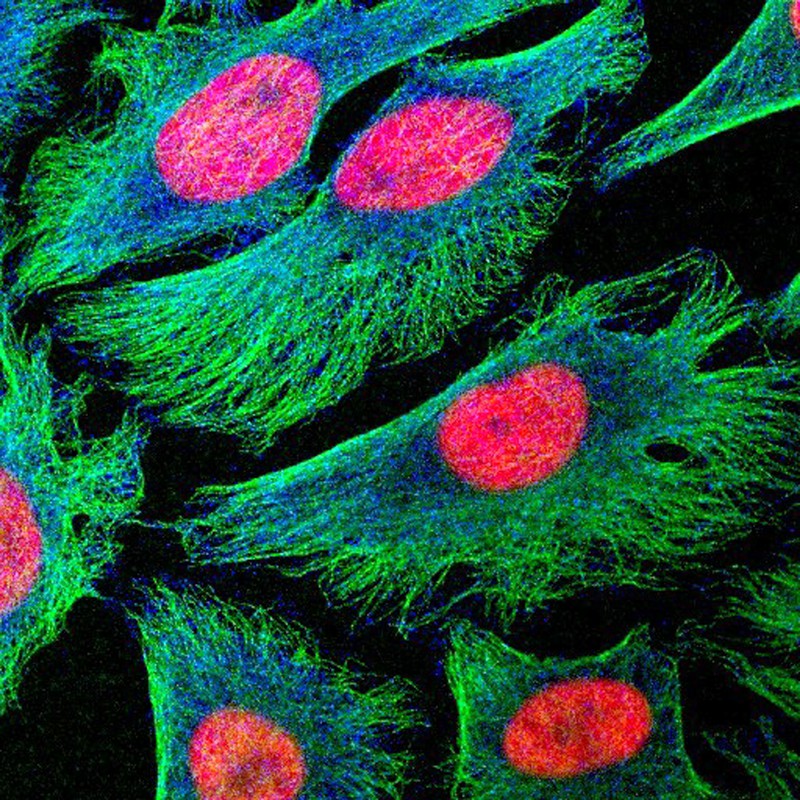

SW480 cells are beautiful – they are all different shapes and sizes. At any one time some will be round like little balls, whilst some will be flat along the base of the flask. Some will be clustered in little groups and some will be in the process of moving away on their own, or dividing, or even dying.

You can see the cells in all their glory here. This (download, 5.2MB) is a video of a ‘scratch wound assay’ – I grew the cells until they covered the surface of the flask, then scratched a line down the middle and watched as the cells moved back into the space. I could watch this video for hours – you can actually see the cells moving and changing shape and dividing.

Each of these cells is incredibly complex. In just one cell, there will be thousands of different processes happening all at the same time – molecules will be working together to turn the genetic code into proteins, proteins will be transporting other molecules into and out of and around the cell, and tiny packages called mitochondria will be producing the cell’s energy. Even dying is complicated for an individual cell, and I studied some of the many processes which can lead to its destruction. There are over 30 trillion cells in the human body: growing, dividing and dying, all at once.

Credit: Matthew Daniels. WellcomeCollection. (CC BY 4.0)

The fact that so many tiny molecules can come together in such intricate ways to form human beings is beyond my understanding. The sheer beauty of cells strengthens my faith in a creator God who has created an incredible world; a God who creates abundantly and extravagantly. I believe that God uses scientific processes such as evolution in his creation and for me, a creator God who can create things which create themselves is awesome.

But SW480 cells are not normal, they are actually colon cancer cells originally taken from a tumour in the 1970s. How can I possibly consider cancer cells to be beautiful? To me, these cells are beautiful despite the fact they are cancerous. All cells in a cancer originated from ‘normal’ body cells, and the beauty I see is the beauty I would see when looking at any type of cell.

As a scientist, working in the lab every day, it was easy to forget that ‘my’ cells came from a cancer. They became like pets that I had to keep happy, well-fed, and clean. But I felt a great sense of responsibility to work to the best of my ability out of respect for the person whose tumour the cells had originally come from.

I still feel a sense of wonder when looking at pictures of ‘my’ cells. I feel honoured to have been able to study them in intricate detail, to watch them grow and move and divide. I feel incredibly privileged to have seen things that no other human has ever seen before and to have been able to learn more about God’s world through these beautiful cells.

Dr Clare Foster is a Public Health Specialty Registrar, currently based at Barnsley Council. Clare started her career as a lab-based scientist, studying cancer cell genomics and proteomics for her PhD at Durham University. She then moved into office-based clinical research roles in Cambridge, studied for an MPhil in Public Health and was awarded a CLAHRC Research Fellowship. As an undergraduate, Clare set up a student group of Christians in Science (CiS) and was involved for many years with the work of CiS as a representative on the national CiS committee.

Dr Clare Foster is a Public Health Specialty Registrar, currently based at Barnsley Council. Clare started her career as a lab-based scientist, studying cancer cell genomics and proteomics for her PhD at Durham University. She then moved into office-based clinical research roles in Cambridge, studied for an MPhil in Public Health and was awarded a CLAHRC Research Fellowship. As an undergraduate, Clare set up a student group of Christians in Science (CiS) and was involved for many years with the work of CiS as a representative on the national CiS committee.