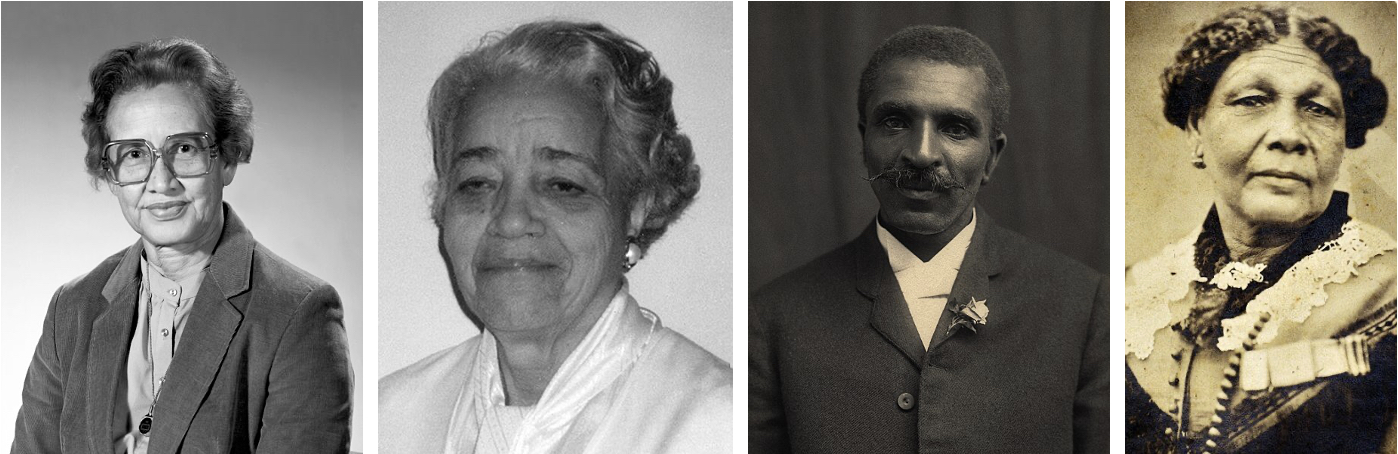

Katherine Johnson, mathematician; Dorothy Johnson Vaughan, mathematician; George Washington Carver, botanist; Mary Jane Seacole, nurse practitioner

Black History month is a time to remember people who are often overlooked but played a key role in society. For example, last month marked the thirtieth anniversary of Dr Mae Jemison’s historic NASA mission as the first African American woman in space. On a similar theme, three Black mathematicians – two of whom were openly Christians – contributed to the moon landings, a story popularised by the film Hidden Figures.

Another hidden element in today’s history of modern science is the contribution of Christian theology – in particular the doctrine of creation.

Today we would correct any child who thought she could learn about the created order by sitting and thinking about how it should be in an ideal world, but that’s what some ancient Greek philosophers believed.

Compare that with Isaac Newton, who wrote ‘we must not seek [knowledge about the laws of nature] from uncertain conjectures, but learn them from observations and experiments’. His science was driven by belief in a creator God who set the ‘laws of nature’ in place.

Mary Seacole, arguably the first nurse practitioner (and not just the first of Afro-Caribbean descent), used the same skill of observation in honing and applying her prodigious knowledge of tropical disease, patient care, and herbal medicine. I was struck by a comment in her 1857 autobiography, ‘The faculty have not yet come to the conclusion that the cholera is contagious…but my people have always considered it to be so’. In questions of science, it’s worth taking note of hard-earned practical experience.

Another contribution of theology to science came from the Christian understanding of the Fall. Francis Bacon, a key figure in the development of the modern scientific method, believed that we can repair some of the effects of the fall through hard work and collaborative experiments (though affirming our need for Jesus’ atoning death and resurrection).

George Washington Carver, a freed slave and (like Seacole) a lifelong Christian, put this into practice in his research on sustainable agriculture and food production in the American South, attributing his insights to God.

History is never simple but it is always worth thinking about why these stories are so often overlooked. By bringing them to light, we can understand more about why we have arrived in a place where science seems to be dominated by white men, and science and faith are said to be in conflict. How can these ideas inform your conversations with scientifically-minded friends, family, or colleagues in the coming weeks?

Ruth Bancewicz

Church Engagement Director, Faraday Institute of Science and Religion

This post is reproduced, with permission, from the London Institute for Contemporary Christianity Connecting With Culture blog.