Wikimedia, Steve Rapport, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

How do you feel about science after eighteen months of pandemic – tired or interested, impressed or cynical – or a bit of everything? The rapid spread of COVID-19 around the world caused the scientific method to be played out in full view. In a short space of time we’ve gone from knowing nothing about the SARS-CoV-2 virus to talking about having PCR tests and comparing vaccinations. We’ve had the opportunity to see some of the process of how scientific data is gathered and shared by researchers around the world, how theories are tested and confirmed or rejected, and how our understanding of a disease and its treatment can become clearer as the data accumulates. Much is still uncertain, and a number of recent polls have shown that most of us are eager for scientific advance to continue.[1]

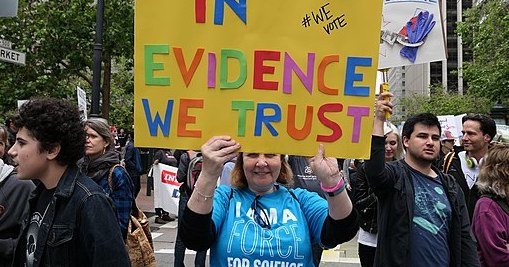

On the other hand, some of us may have become more wary or distrustful of being encouraged to ‘trust the science’,[2] perhaps angry or disillusioned at the decisions based (more or less, rightly or wrongly) on scientific knowledge that disrupt our lives, causing us heartache and worry. It is also very easy to get science (a specific set of tools used to investigate the world) mixed up with scientism (valuing science far more than other types of knowledge, perhaps even seeing it as the only source of knowledge).[3]

This pandemic has demonstrated how important it is to recognise that ideology or worldview, and questions of ethics or values, meaning and purpose are hugely influential in our interpretation of scientific data – and at times in the process of experimentation itself. Should we trial a vaccine in Spain or South Africa? Is this vaccine safe enough to administer to the general population? Should vaccination be made compulsory? The data don’t tell us what to do. Different governments look at the same figures and come up with different policies, for reasons we may only guess at. We are all influenced by different reports, individuals or media channels, and react to guidelines in a variety of ways. So when we are encouraged to ‘trust the science’ in our ongoing response to the pandemic, or in the run-up to COP26, how can the Church respond?

The first three verses of Psalm eight affirm that the heavens and the earth belong to God. He alone is worthy of worship. The whole biblical story affirms that God is the only one in whom we can have complete faith, and for billions of people around the world that belief underpins the whole of life. For reasons I don’t have time to explain here, I don’t trust anything or anyone else in the same way as I trust the one the Psalmist calls Lord.

On the other hand, I do put a certain amount of trust in things other than God. I can have faith in a plane, a body of knowledge, or a person. This kind of trust is within narrower limits because I know that air travel involves hazards, a body of knowledge will contain some mistakes, and every human[4] is fallible. I trust science to some extent because it involves careful observation and measurement, collecting different kinds of evidence. Data is interpreted, and competing interpretations are tried out. We summarise our findings in general principles or mathematical equations. Scientists keep each other accountable by looking critically at each other’s work. Our knowledge is always provisional. You can’t prove anything scientifically because we only deal in evidence, but there must always be the potential to disprove a theory or it’s not science. The aim of the scientific community is to keep getting nearer to the truth about the way the world is. Overall, I believe this method is reliable and worth supporting, but that only God is completely trustworthy.

If science is so useful, can it help us to see God? Verse one of Psalm eight speaks of God’s glory being visible to us in his creation. Scientific investigation can reveal even more of these wonders. We can see images of stars and galaxies, individual cells, and in recent years even atoms and molecules. I find this sort of data helpful in reminding me that the Creator must be very great, powerful and rational. But the scientific method is about finding evidence for how things work, not proof, and our theories are always being updated, so I don’t want to base my faith largely on scientific knowledge. Also, while scientific data can give some clues about the mechanisms of how things work, they can’t answer questions of meaning and purpose. We can pick up a few vague hints about God using science, and fuel our worship with our exploration of his wonderful creation, but to see his fullest revelation of himself we need to look to the person of Jesus.

Images of vast galaxies can make us feel small and insignificant, but verses four to eight tell us that God has placed humankind in a position of responsibility. We are to rule the Earth. I believe that scientific knowledge, used wisely and within its proper limits, can be part of what helps us to rule well. The process of scientific discovery can be a bit like a blurry image coming into focus. The more we learn, the better we can usually see what’s going on, and hopefully the easier it is to decide on a course of action.

For example, verses seven and eight mention flocks and herds, birds and fish. Our relationship with domesticated animals now involves large amounts of knowledge about how they behave, their needs, and how we can benefit from them in terms of food, clothing, transport, and so on. Today we can trust that if we keep cows in the right way we will probably get some milk, or if we look after hens properly we will hopefully have eggs. If we fail to look after animals well they will not thrive, and their presence may even harm our own health – for example in the transmission of disease.[5] Also, if we keep too many animals[6] they can do serious damage to the environment. While science will not save the world, it can give all of us some ideas about how to look after it.

So the message for the church that I take from this Psalm, in the response to the question ‘Should we have faith in science?’, is that the Lord God is supreme. The whole biblical message teaches that he is the only one we can trust completely. Science does have its place, not least because it can help us praise God for his amazing creation. As we take our place and obey his command to rule over the earth, science can help us to do that wisely.

Discussion questions

How do you feel about science just now? (Either before you read this article, or afterwards). What are you grateful for? What do you find difficult?

Have you come across the concept of scientism before? Can you think of any examples of scientism in things you have seen or read in the last few days?

Do you find the distinction between science and questions of meaning or value helpful?

What encourages you to put faith in God?

What helps, or would help, you feel you could trust the process of scientific enquiry?

Which parts of the created order help remind you about God?

Can you think of several ways in which scientific knowledge helps us, or could help us, to rule over creation wisely?

How can you and others in your church work together to care of creation? e.g. can you organise a clothing swap, set up a repair café, or campaign for better public transport/cycle lanes in your area?

Taking it further

Faraday Churches: Introductory article: Science and the Church

Faraday Churches: Can Science Prove God Exists?

Faraday Churches: Should Christians Be Concerned About the Environment?

BioLogos: Should We Trust Science?

BioLogos: How Christians can help end the pandemic

BioLogos: Vaccine Q&A with Dr Francis Collins

A Rocha International: Conservation and Hope

John Wyatt: series of podcasts on coronavirus vaccines

[1] https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2021/03/12/has-the-pandemic-changed-public-attitudes-about-science/

[2] https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0252892

[3] https://www.aaas.org/programs/dialogue-science-ethics-and-religion/what-scientism

[4] With one significant exception…

[5] https://modernfarmer.com/2021/06/how-can-we-prevent-the-next-zoonotic-disease-outbreak/

[6] Humans and their livestock now account for more terrestrial biomass than wild animals, e.g. https://www.pnas.org/content/115/25/6506