I want to share with you some of what must be the most odd-looking animals of all time. Of course they only look strange because most of us have never encountered them before. They lived in the sea more than 500 million years ago, were preserved in the mud that engulfed them at their death, and ended up as part of the Rocky Mountain Range, northern Greenland, and south-east China.

The creatures in question are named after the place where they were first found, the Burgess Shale, which lies between Mount Field and Wapta Mountain in Yoho National Park, Canada. They are thought to have lived in fairly deep water a short distance from the ancient continent of Laurentia. [1] At that time there was very little life on the land, but the oceans were teeming with animals and plants.

Many of the Burgess Shale animals were primitive worms, burrowing in the mud on the sea floor. Above them grew sponges – some fabulously spiky and others branched like comic-book cacti, providing a stable habitat for other creatures. Some of the animals embedded in the mud might have looked like ferns or flowers. Thaumaptilon walcotti had tongue or feather-like fronds and perhaps disappeared into its burrow when a predator approached, while Dinomischus isolatus was a little like an armour-plated sea anemone.

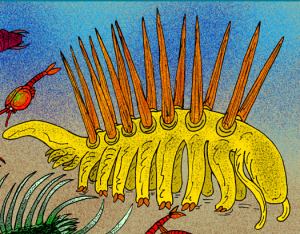

In between these filter feeders, small creatures just a few cm long crept or scurried around on jointed legs. Most of these bottom-dwellers were arthropods [2], including the familiar trilobites and variations on that theme, such as beautiful Marrella Splendens with its long sweeping antennae. Some looked more like caterpillars, and Hallucigena is one of the strangest-looking of these, with a frightening row of spikes on its back and a head and tail that are difficult to tell apart.

Many of the animals discovered in the Burgess Shale cannot be fitted into any existing categories. Opabinia is a classic example, with five eyes and a long trunk with a feeding claw at its far end. Wiwaxia has a molluscs’s soft foot, but also a spiky hair-do of long spines and short scales. At about a metre long, Anomalocaris is the largest of the Burgess fossils. This fearsome lobster-like creature had two jointed arms that pushed food into its oddly plate-shaped mouth.

This array of weird-looking creatures might seem baffling – some might think them a sign that evolution acts in random ways. Professor Simon Conway Morris, who was one of the palaeontologists who studied these animals, thinks differently. In previous blogs I have explained his idea that the pathways of evolution often converge on similar solutions – the camera eye, jointed legs and green plants being just a few examples.

The discovery of these fossils has opened our eyes to the immense variety of animals that were present well before dinosaurs or large mammals roamed the earth. If the size and scale of the universe are a fitting prelude to God’s own arrival on Earth, then these creatures tell another tale.

For a person of faith, they perhaps demonstrate God’s patient creativity – that he could use such long, slow and seemingly meandering processes in a purposeful way, to bring about the full diversity of life on earth.

For more on the Burgess Shale discoveries, see Simon Conway Morris, The Crucible of Creation: The Burgess Shale and the Rise of Animals

[1] Before it split into North America and Greenland, and some of the rocks that were once underwater were exposed on land.

[2] Arthropods include the crabs, insects and spiders.