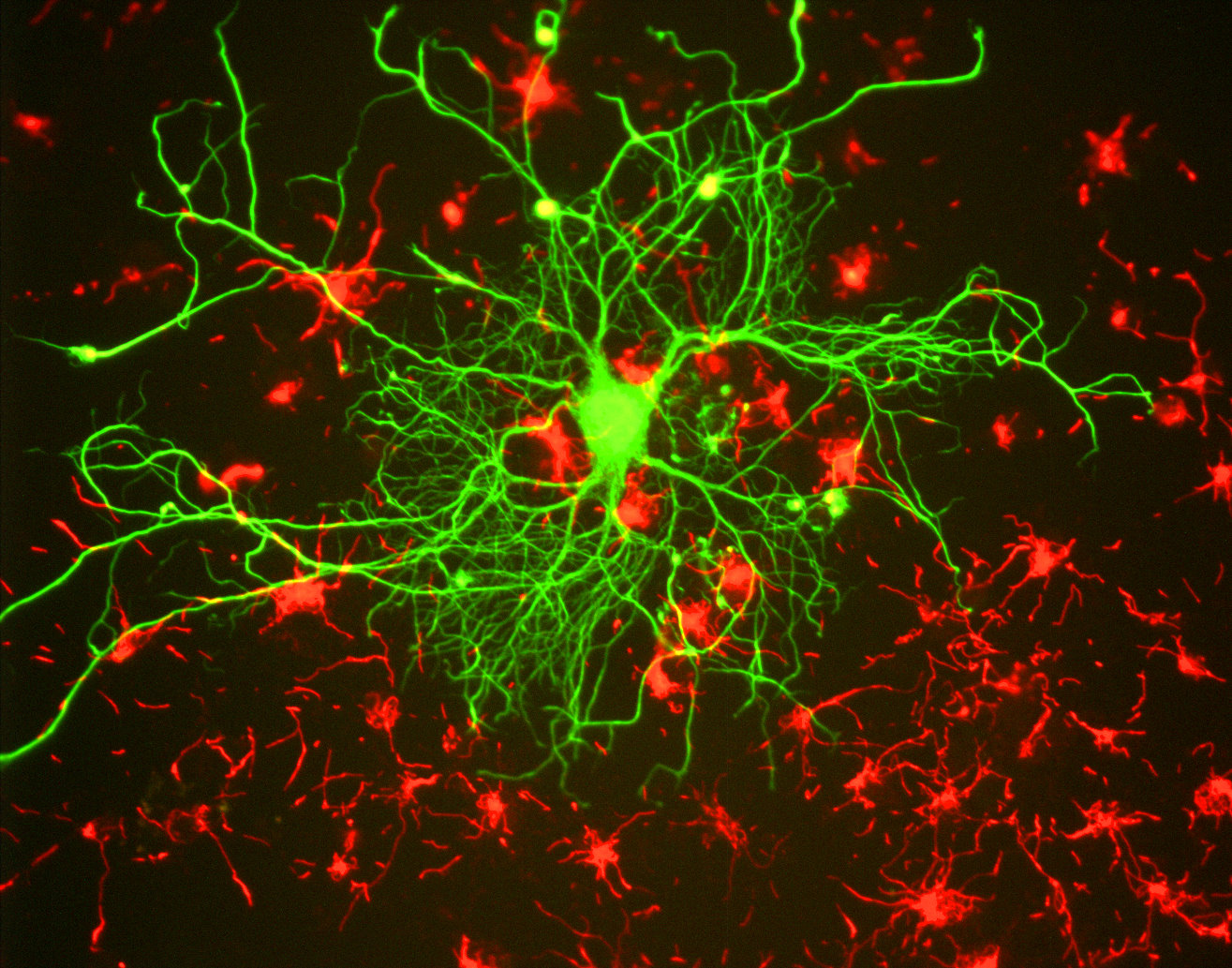

Cortical neuron By GerryShaw (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Last Friday, Professor Irene Tracey, spoke at the Faraday Institute about Imaging States in Pain and Religion. Tracey is the Nuffield Professor of Anaesthetic Science at Oxford University. She also heads up the Pain Analgesia-Anaesthesia Imaging Neuroscience (P.A.I.N) Group in the department of Clinical Neurosciences, where the focus is on understanding what is happening in the brain when we feel pain.

Human brain illustrated with millions of small nerves by Ars Electronica – Flickr. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Tracey explained that our perception of pain is a combination of prior expectation plus actual sensation. This system is efficient for our brains, because it results in a quick assessment and reaction, but it can have its disadvantages. She told a story of a builder who felt excruciating pain when a nail penetrated his boot. When he arrived at hospital and his boot was cut off, it turned out that the nail had passed between his toes.

The advantages of our pain-perception systems far outweigh the disadvantages, as any parent knows. Distraction is a wonderful way to help a child endure an injection, a grazed knee, or even something more serious. The pain modulation system is regulated through the brainstem, in response to signals from other parts of the brain. So when Mum tells Johnny it will just be a little stinging feeling, Dad kisses that knee better, or you go into work with a sprained ankle and forget all about it, the body is releasing strong pain-relief in the form of natural opioids.

Until recently, medical researchers used to publish articles about how to maximise what we now call the placebo effect. If someone is told they have been given a great drug, they are likely to feel a bit better. Doctors also knew the importance of having a good relationship with their patients as long ago as Hippocrates. Since the 1950’s, however, placebos have been thrown out of medicine. But has the baby been thrown out with the bathwater?

Temazepam 10mg tablets-1 By Adam from UK [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

One of Tracey’s passions is to help those running clinical trials to see that giving a patient a placebo is not the same as giving them nothing. The fact that many new drugs don’t do much better that the placebo effect is not terrible, because the body’s own painkillers are very strong. This is not a suggestion that doctors should go back to prescribing white tablets in unlabelled bottles. I’m sure there are more sophisticated ways to put this research into practice, but it’s good to know that even a parent’s ‘kiss it better’ approach is actually very powerful.

By Gentile da Fabriano [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

This is only the beginning of developing a clearer understanding of pain, but it promises much in terms of improving medicine, and also helping us to understand ourselves and our beliefs. As a Christian myself, I believe that the effects of my prayers are more than a self-help method. It will be interesting to see the results if anyone chooses to continue Tracey’s work on prayer and pain.

[i] This was in a research study with consenting volunteers.