Professor J. Richard Middleton feels called to help the church interpret the Bible well (see his first podcast). In his seminar at the Faraday Institute last month, he outlined what he thinks the first two chapters of Genesis say about the origin of humankind.

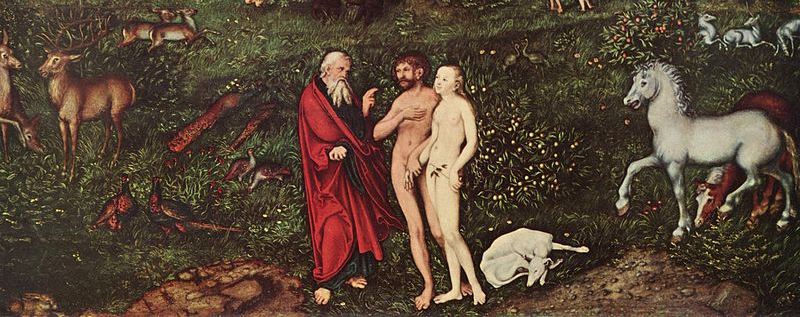

In ancient Hebrew, the words that are often translated into the names Adam and Eve can have more than one meaning. They can be personal names, or they can mean something less personal: human and woman. For example the Hebrew word ’ādām, translated ‘man’ or ‘Adam’ depending on the context, is similar to the word ’ădāmâ, meaning earth – in the same way that ‘human’ derives from ‘humus’, or soil. So there is a play on words right there in the first few chapters of the Bible. In Genesis, ’ādām is used in the generic sense until chapter five.

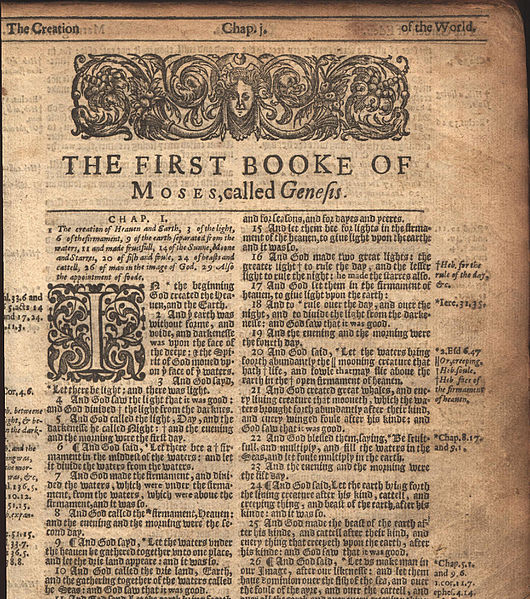

By Classicalsteve (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Chapters one and five of Genesis mention that people are made ‘in the image of God’. Some people have taken this to mean that we are radically different from the other animals. For Richard, the difference is not in the differences between us and any other creature, but in what we are to do. We are called to represent God’s presence on earth and rule on his behalf. We are to work the earth and transform it as responsible stewards, not tyrants.

Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden by Wenzel Peter, Vatican Museum photographed by faungg’s photos. Flickr. (CC BY-ND 2.0)

So the biblical picture is of some continuity between humans and other creatures. Genesis includes people with every other land animal in the same figurative day of creation. Both originate from the ground, and receive the same breath from God. None of this is a scientific story, but a theological one: we are all creatures together. In Psalm 104, humans and other animals are also paired together in the same verse, and the word ‘formed’ is used of both the mythical leviathan and human beings. In the book of Job, the ‘Behemoth’ is said to be made along with us. All of these passages suggest that a common ancestor for people and other animals is more than compatible with the biblical narrative.

Interestingly, we may be made ‘in God’s image’ but other parts of creation are also shown to represent God in different ways. For example, in Genesis one God is said to separate the waters above from the waters below, but later on in the chapter he delegates that job to the ‘firmament’, which is sometimes translated as sky. The sun and moon are also delegated the jobs of separating day and night. When the land, sea and sky were populated with living things, the creatures were given fertility and asked to fill the world. In a sense, humans are not the only part of God’s creation that shares his creative ability. And just as humans are asked to rule over the earth, the sun and moon are also given the task of ruling in the heavens.

Cropped detail from: Creation of Adam by Michelangelo [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

For Richard Middleton, science doesn’t determine how he interprets scripture, but it can help. Evolutionary biology has helped him to notice things in scripture that he hadn’t spotted before. It also might work the other way around – perhaps the Bible can prime us to what evolutionary biology might says about us? For example, did the period of rapid cultural growth in our past herald the arrival of the image of God, when God entered into relationship with us and called us to a specific role? It’s a huge speculation, but it could fit.

NEW: Be encouraged and equipped with a new bite-sized resource every month, including a short video, article and discussion questions. Join for free on Patreon for access to each month’s set of material, addressing a different topic/Bible passage each month AND two podcasts with experts on the same topic.

If you would like to support this work financially (£6/month) you will also receive these benefits:

- access to two live podcast recordings each month, where you can ask questions of experts in the topics covered and meet like-minded people.

You can listen to or watch Richard’s full seminar on the Faraday website.

Further information

- Richard Middleton, A New Heaven and a New Earth: Reclaiming Biblical Eschatology (Baker Academic, 2014)

- Richard Middleton, The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1 (Brazos, 2005)

Richard is part of the ‘BioLogos Voices’ speakers bureau.

© Faraday Institute

Ruth Bancewicz is a Senior Research Associate at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where she works on the positive interaction between science and faith. After studying Genetics at Aberdeen University, she completed a PhD at Edinburgh University. She spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology at Edinburgh University, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. Ruth arrived at The Faraday Institute in 2006, and is currently a trustee of Christians in Science.