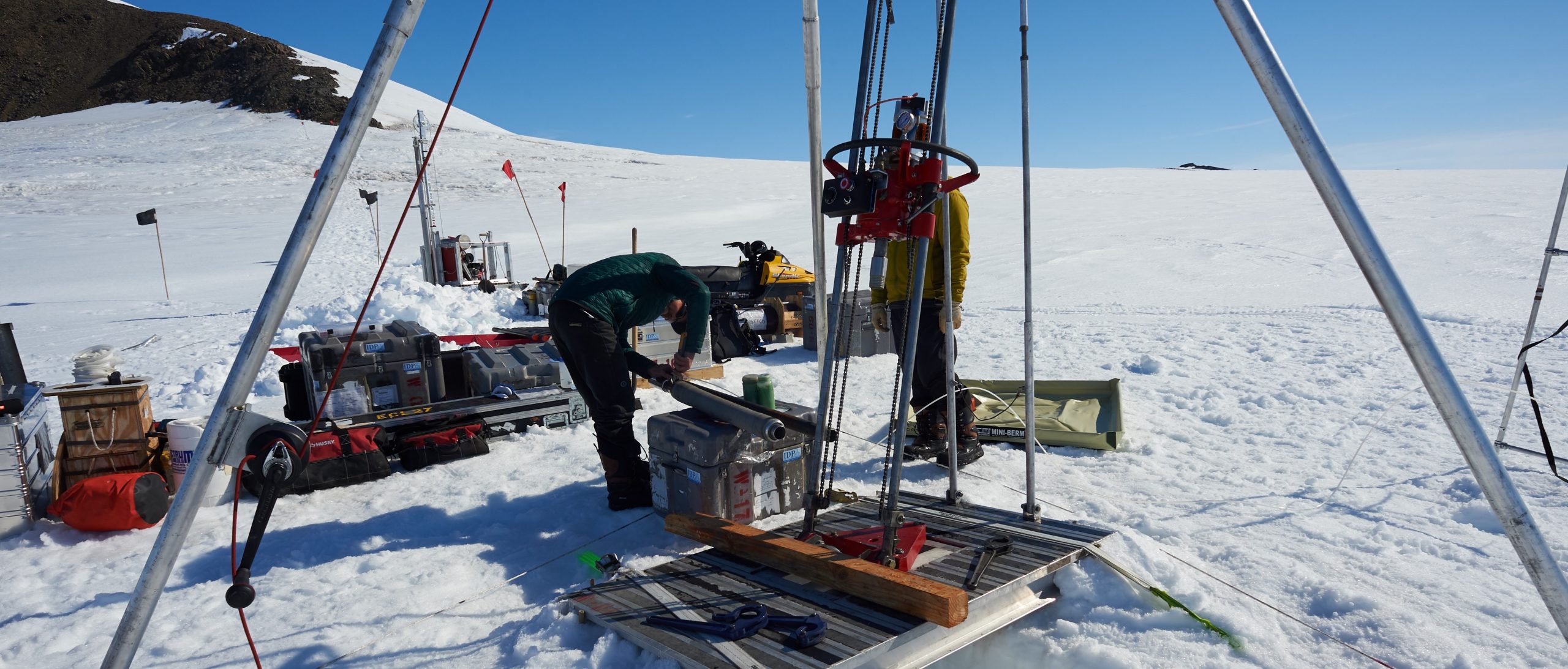

© Greg Balco (International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration)

Joanne is studying the mighty Thwaite’s glacier in Antarctica. She drills down into the ice, collecting rock samples for laboratory analysis. Her team will run tests that tell them when the rocks were last exposed to air, providing some clues about how the ice sheet has expanded and contracted over the centuries. Ultimately they hope to gather enough data to be able to predict how glaciers like Thwaites might respond to current climate conditions, and the impact they may have on sea level over the coming decades.

What science is

Science is all about gathering evidence for physical phenomena by making measurements and observations. Looking at these data, scientists can develop general principles about the way things are, often describing them mathematically. In this way we have learned that glaciers shape landscapes, that water is made out of hydrogen and oxygen, and that energy and mass are interchangeable (described by the famous equation E=mc2).

Scientists need creativity and imagination to solve problems and come up with new ideas. They need to work together and test each other’s proposals, because every scientific discovery is provisional – to disprove the statement that ‘all swans are white’, you just need to find a different coloured swan. There are always blind alleys, mistakes, and setbacks in science, but over time any well-run programme of scientific research should hopefully be getting nearer to the truth.

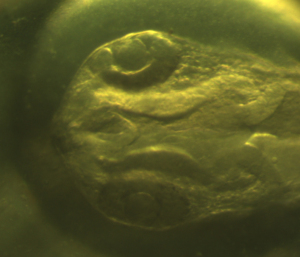

© Jordan Parrett

If you have had the privilege of swimming around a relatively undamaged coral reef, you will have been amazed by the variety of creatures you see: brightly coloured coral, fish of all shapes and sizes, algae, sponges, clams, sea urchins, and so-on. You can count the number of species and how abundant each one is, you can observe how they reproduce and interact together, and build up a detailed scientific picture of how a reef is built. But there are other ways of looking at the world. You can also ask questions about whether it is worth protecting, and the impact of its beauty on human observers, that require more philosophical or theological answers.

Worshipping God with science

For the Christian, everything is created by God. He is the primary cause, who has revealed his purposes to us – and these are recorded in the Bible. We can also study the secondary causes of physical forces, chemical reactions and interactions of living organisms that shape life on Earth. So we can find some scientific clues about the mechanisms behind the origin of a solar system with rocky planets, the build-up of water and organic molecules, the origin of life, and what it takes for a coral reef to form on the sea floor. All of these processes are sustained by God, and only he can create from nothing in the first place. Our understanding of mechanism and meaning are complementary.

As rational creatures made in God’s image, we can enjoy both theological and scientific knowledge by exploring the world God created, acknowledging him as the ultimate source of everything we find. We can worship God with science.

So, science can support our theology, reminding us how wonderful the creator must be to make such amazing things. We can also give theological reasons for doing science. We explore God’s creation because it has value. Passages throughout the Bible tell us that creation is very good, it is fruitful and ordered, praising and glorifying God. God didn’t have to create in any particular way. To discover what he does we need to take a look, and I believe that exploration honours him in the same way that a child enjoying a gift brings pleasure to the giver.

We also need to think about what we can learn from creation. We know that God created, that Christ was there in the beginning, that all creation praises God, and that one day everything will be renewed because of Christ’s death and resurrection. But what can we learn by looking at creation itself?

The theologian and scientist Alister McGrath has written that theology is like a lens, bringing into focus everything we learn using the tools of science. Science is consistent with theology, making sense of the order and beauty we see. The fact that the universe appears to have had a beginning resonates with my belief in a creator. The fruitfulness of life on earth, and its increasing complexity, are explained by the God’s purposes for creation. None of these resonances between science and theology are proof for God’s existence. Other worldviews also have explanations for these data, but they are consistent with the existence of a powerful, loving, purposeful God.

So when I visit a piece of ancient forest I can praise God alongside the trees, animals, plants and fungi that inhabit every niche. For example, I know there are countless worms, bacteria, and other hidden or microscopic creatures on and under every surface. Each one praises God by simply being itself. My scientific studies can help me appreciate a lichen or fruiting slime mould, and thank God that cooperation is one of the great driving forces behind the development of life on earth. I can also thank him for the processes in my own body that share so much with the organisms around me. My scientific knowledge helps me to praise God, inspired by my fellow creatures – the birds and other animals that are making their presence known by their different noises all around me – as well as the less animated plants, and even rocks or water. These things are praising God even if I’m not there, but I can join in – in my own way. The Psalms are full of descriptions of the praise that creation offers to God, and we can still take part in it today.

So when I visit a piece of ancient forest I can praise God alongside the trees, animals, plants and fungi that inhabit every niche. For example, I know there are countless worms, bacteria, and other hidden or microscopic creatures on and under every surface. Each one praises God by simply being itself. My scientific studies can help me appreciate a lichen or fruiting slime mould, and thank God that cooperation is one of the great driving forces behind the development of life on earth. I can also thank him for the processes in my own body that share so much with the organisms around me. My scientific knowledge helps me to praise God, inspired by my fellow creatures – the birds and other animals that are making their presence known by their different noises all around me – as well as the less animated plants, and even rocks or water. These things are praising God even if I’m not there, but I can join in – in my own way. The Psalms are full of descriptions of the praise that creation offers to God, and we can still take part in it today.

Serving God with Science

There is of course practical value to science. Many of the creation passages tell us that we should tend and keep the earth, and scientific knowledge helps us to do that more effectively – as well as helping other people. The Wisdom literature tells us that by looking at creation we can learn some useful lessons about how to live. Like any type of work, scientific research is also a crucible for character formation, and provides opportunities to demonstrate what it looks like to follow Christ.

My own research was in genetics, looking at the ways in which environmental impacts can affect the development of an embryo. I watched as single fertilised eggs developed into beautiful zebrafish, learning how their eyes take shape and become wonderfully iridescent. Through working with a closely-knit team I learned about patience, persistence, and cooperation. My research will hopefully inform the work of medical researchers, and help others in the future as they make decisions about release of chemicals into the environment. I no longer use my scientific skills in the lab, but I am grateful that I had the opportunity to worship God with science.

My own research was in genetics, looking at the ways in which environmental impacts can affect the development of an embryo. I watched as single fertilised eggs developed into beautiful zebrafish, learning how their eyes take shape and become wonderfully iridescent. Through working with a closely-knit team I learned about patience, persistence, and cooperation. My research will hopefully inform the work of medical researchers, and help others in the future as they make decisions about release of chemicals into the environment. I no longer use my scientific skills in the lab, but I am grateful that I had the opportunity to worship God with science.

Science can be used to do a great deal of good, but once knowledge is gained the researchers often have very little say in how others use it. For example, an immense amount of scientific research has enabled the development of smartphones. I am very grateful indeed to have a tiny computer in my pocket that can help me stay in touch with family and friends, learn new things, capture images, and find out where I am. But scientific knowledge can also be harnessed in more destructive ways. I am acutely aware that my phone can distract me, give me access to unhelpful information, or enable me to buy things I don’t need. Science helps put the tool in my hand, but it cannot tell me how to use it. I have to look to other sources of wisdom to learn how to live well.

Scientists of Faith

My experiences are not so different from scientists[1] in the past, who saw their work as part of their service to God. The founders of science as we know it, including Francis Bacon and Galileo Galilei, gave theological reasons for investigating the world. The result was that Christian theology contributed to the assumptions that lie behind science today, including the ideas that we are rational and our investigations are worthwhile, and the expectation that there will be regular mechanisms behind physical events.

For Johannes Kepler, the astronomer who worked out that the planets have elliptical orbits, “Our worship is all the more deep, the more clearly we recognise the creation and all its goodness. Indeed how many songs did David sing…He received the ideas for his songs from the admiring observation of the skies.”

In my own experience, and my investigation of other scientists’ lives, I have found that science reveals more of the beauty of creation, helping us to worship God and appreciate his beauty. The creativity of science is an outlet for our God-given creativity. When we feel a sense of wonder that makes us investigate creation for ourselves, we are exercising intellectual muscles that we also use when thinking about God, and asking questions about his nature and purposes. Imagination is important for forming a view of the world, which we then test with experiences or other ways of investigating reality. Finally, awe – being transfixed in amazement – is both the reward for our explorations and a mental stretch that takes us beyond the mundane. We can sometimes feel overwhelmed by knowing more than our minds can take in – dazzled by the bright light of how much we can understand about the world – and this can fuel bigger questions about the meaning and purpose of the universe.

After that introduction, it’s perhaps not surprising to find out that there are many Christians in the sciences. There is far more commitment to faith in the scientific community than some might expect. At the same time, the number of scientists who believe in a god and attend weekly services seems to be about two-thirds of the number in the general population, and fewer have affiliated with a particular faith group.[2] There is something here for church leaders to celebrate, but we could also spend more time affirming the very positive relationship that can exist between Christian faith and science. If more Christians are attracted to science, and more scientists can see that they don’t have to choose between science and faith, there might be more people of faith in science in the future.

| UK general population[3] | UK-based scientists[4] | |

| Belief in a god | 72% | 54.7% |

| Weekly religious services | 14%[5] | 9% |

| Religious affiliation | 67% | 37% |

How Churches can Engage with Science

If Christian faith provides a good foundation for doing science, and if science provides a wonderful way to enjoy, benefit from and serve the Creator and his creation, then how can churches engage with science?

First of all, it’s good to know where to go to be equipped to interact with science in helpful way. There are plenty of resources provided on the churches@faraday section of the Faraday Institute website, as well as the other organisations we recommend. Whether you want to become a science-faith geek, or just know where to go if a question comes up, this is a great place to start.

Another easy place to start is by injecting a bit of wonder into your services and other times of prayer and focussed worship. With beautiful images online, scientific discoveries in the news, and science graduates in many churches it should be well within the reach of the average church to do something to fuel our sense of awe.

Another easy place to start is by injecting a bit of wonder into your services and other times of prayer and focussed worship. With beautiful images online, scientific discoveries in the news, and science graduates in many churches it should be well within the reach of the average church to do something to fuel our sense of awe.

Having made that start, it’s good to give time to theological reflection on science, such as our attitudes to creation or what it means to be made in the image of God. We also need to pay attention to areas of science that demand a theological response, such as climate change or astronomy. Regular activities such as home groups, youth clubs, and community activities provide a great setting for exploring these types of questions. Injecting some science into existing activities can be simple to organise and reach many people – particularly those who might think science isn’t for them. It can also be much easier to have an open and honest discussion in a familiar setting where people already know each other.

Having seen the statistics, you will now appreciate how vital it is for churches to give some space and time to support both working scientists or science teachers, and the next generation who are studying science at school or university. There is a great need to affirm the value of science as a career.

The church can also use science to help us care for people and the rest of creation. It’s almost impossible to separate out these two: people are both affected by and affect the whole of creation. The Bible is very clear that one of our primary callings is to tend and keep the world, and doing this today is a demonstration of the hope and love that we have as Christians. As well as practical action, we can speak up for the vulnerable, whether that is a teenager threatened by the damaging effects of new technology, or a whole community seeing its environment degraded and lacking the resources to change the situation.

Finally, the church can reach out in more general ways, having conversations and running events that help people outside of the church to understand that science works well within a Christian worldview. We can discuss the big questions that science raises about meaning and purpose, and any issues and objections that people raise.

There is plenty to choose from, and each church will find a different natural starting point. Each of our church communities enjoy a unique range of opportunities, and wrestle with a different set of challenges. Whether you start with a few projected pictures during your sung worship, or organise a big event, the important thing is to keep engaging with science at regular intervals.

We hope you enjoy exploring the <>resources <LINK> on churches@faraday, and are <>inspired by the stories <LINK> from churches that have been engaging with science in different ways. Do <>let us know <LINK> about your own church-based adventures with science!

[1] Although these people would not have called themselves scientists. Until relatively recently they would have called themselves Natural Philosophers.

[2] I personally put the last figure down to the contrary nature of academic types in general!

[3] Statistics from the UK census, 2011

[4] From a survey of 1,500 UK-based biologists & physicists by Sociologist Elaine Howard Ecklund and her team, 2011-2012

[5] British Social Attitudes Survey 2016

© Faraday Institute

Ruth Bancewicz is Church Engagement Director at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion. She studied Genetics at Aberdeen and Edinburgh Universities, and spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology in Edinburgh, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. Ruth is a trustee of Christians in Science, and a Fellow of their US counterpart – the American Scientific Affiliation.